Here are some highlights and takeaways from our 2023 World Bank study on Digital Tools for Better Governance in Africa. This was a collaboration between the Governance, Digital Development, and Finance global practices at the World Bank. I’ll cover Volume 1 here and say more about the other papers in the study later.

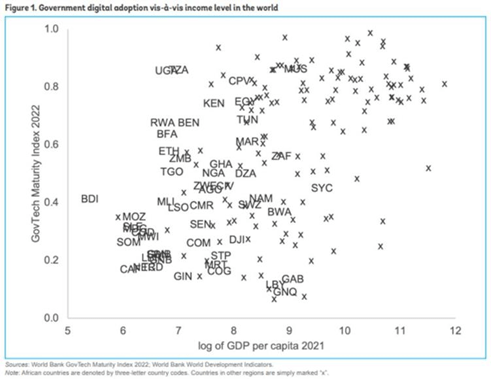

First, the big picture: How do countries in Africa compare? We looked at the GovTech Maturity Index 2022 and mapped this against log of GDP per capita. (Xs are non-African countries.) There is wide variation across countries in Africa in the use of digital tools for better governance, but this seems more a factor of income level than anything else. African countries are largely in line with countries in other regions with similar income levels, and some African countries are out in front.

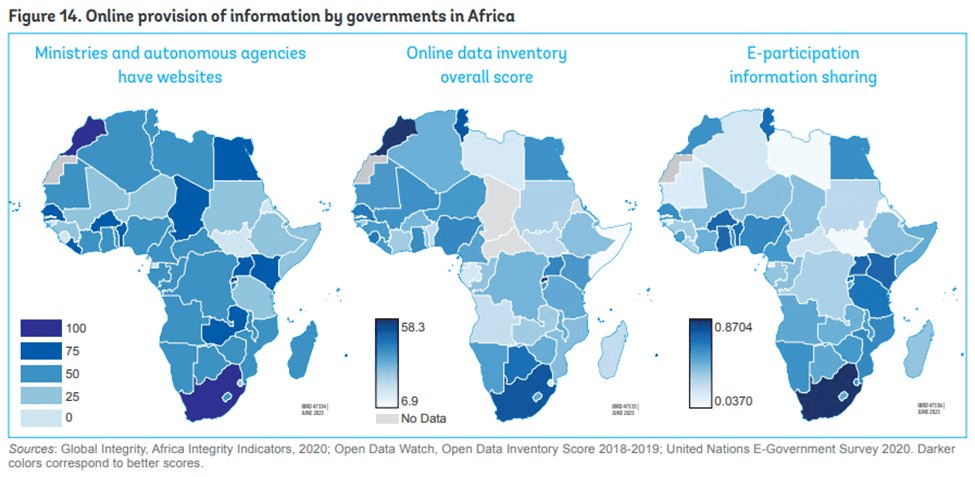

We looked at the use of digital tools for online provision of information, one of the most fundamental and obvious governance-related uses of digital tools. Countries are generally more advanced in their adoption of the most basic functions, like having websites, and somewhat less so for the depth and quality of information availability.

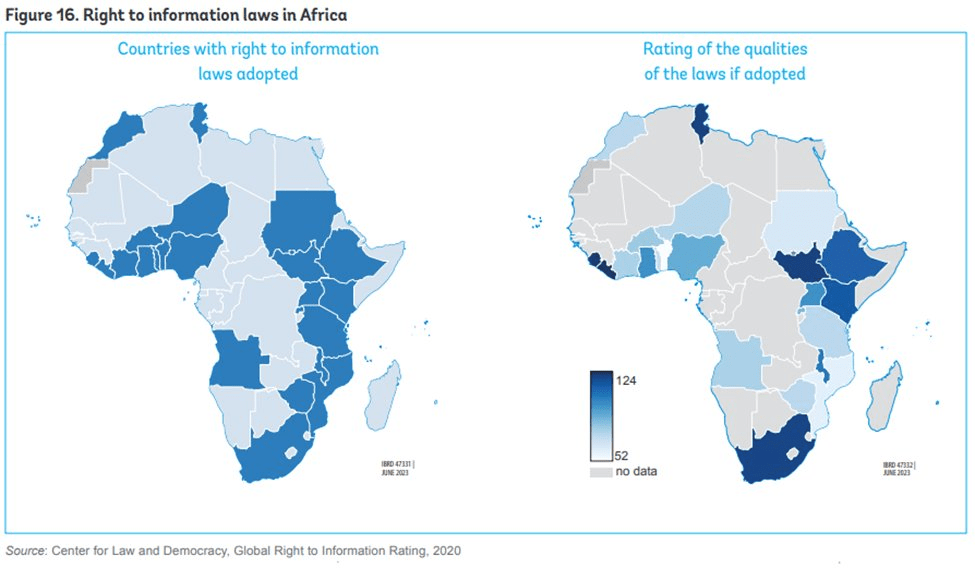

Following another important World Bank study—WDR 2016 Digital Dividends—we looked at the “analog complements” of digitization, things like skills and legal framework. How effective can digital provision of information be if there is no legal obligation to make information available in the first place? In fact, access to information legislation is weak in most countries in Africa.

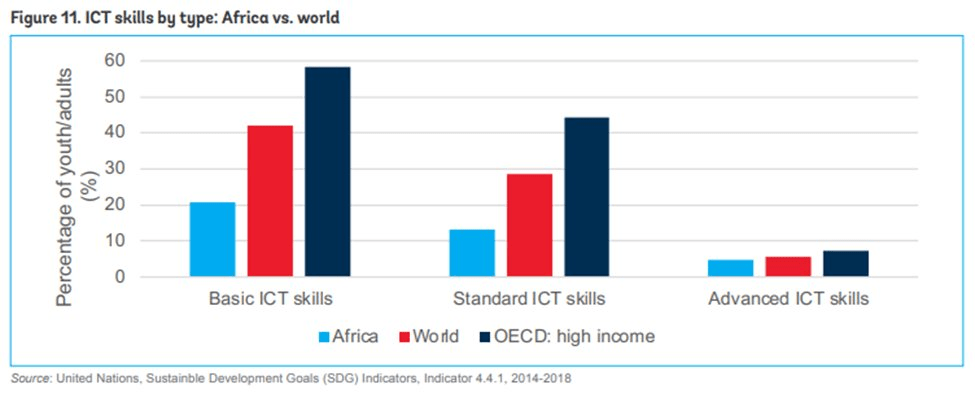

Other analog complements, such as ICT-related skills, are also needed to reach the potential for digital tools for better governance. Again, we find that the continent as a group lags other regions in this regard. Even basic interoperability of systems remains a challenge.

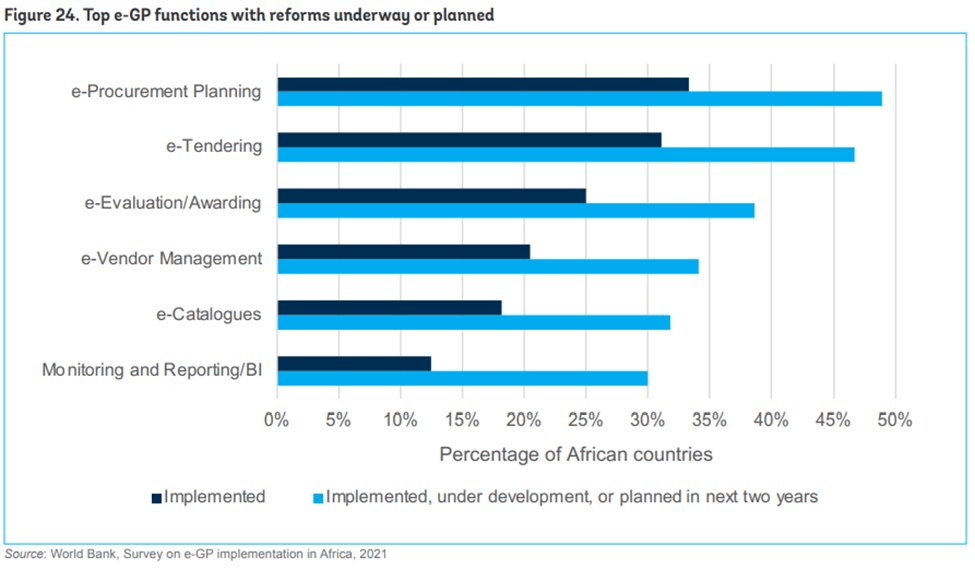

What about specific applications of digital tools for governance? Electronic government procurement (eGP) is among the most promising, offering efficiency, transparency, and control of corruption. Among African countries, eGP functionality is growing.

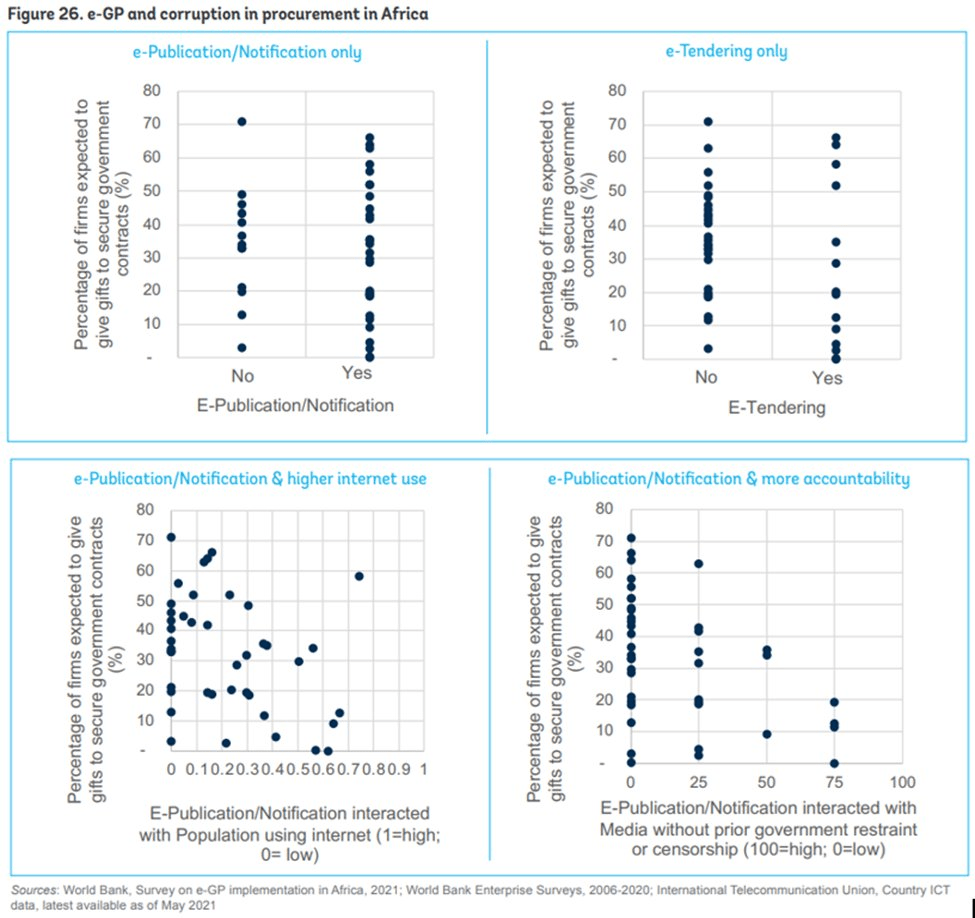

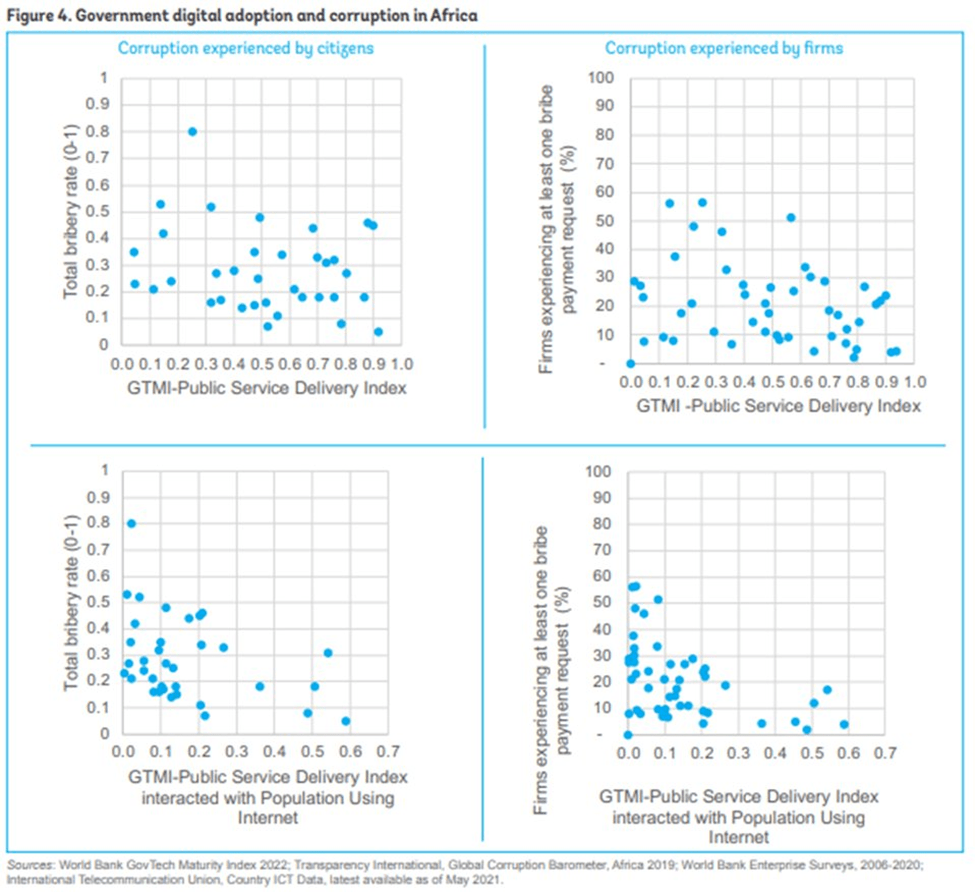

Better outcomes, like lower corruption, depend on availability of digital access and complementary accountability institutions. (Usual caveats for all scatters!) The mere existence of eGP functions like e-publication and e-tendering are not correlated with lower levels of corruption at the country level; unless, that is, one considers the interaction with other basic capabilities like access to internet and free media.

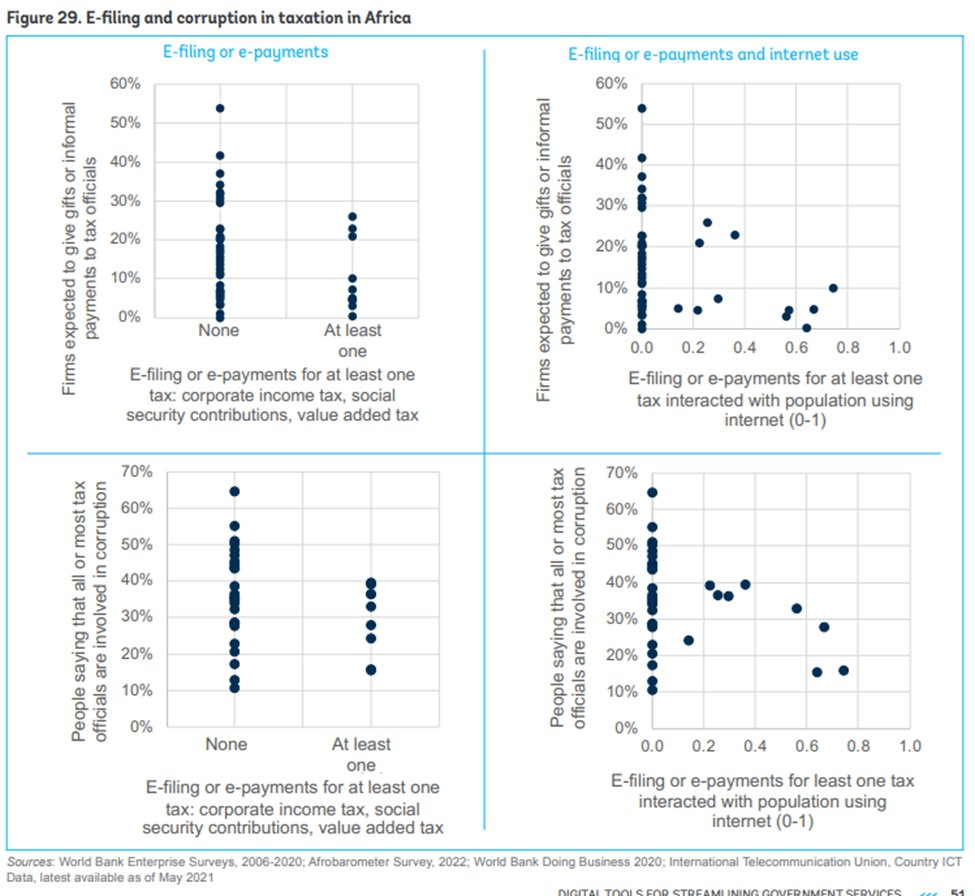

Other digital tools for better governance, such as those related to taxes, are also correlated with lower levels of corruption—especially where internet use is more widespread. Tools like e-filing of taxes and online payments of taxes are associated with lower corruption related to tax, amplified when there is greater internet access.

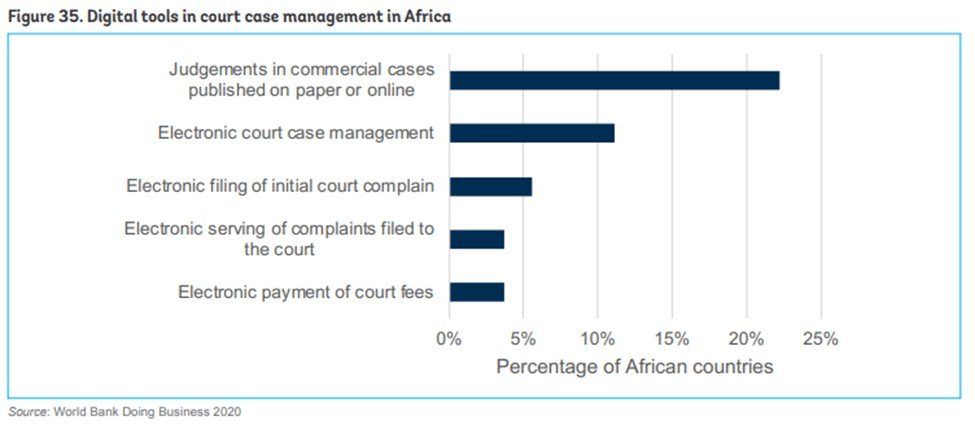

Digital tools also hold promise for other aspects of governance, such as in the judiciary. How widely are digital tools used for this purpose? As it turns out, not very widely at all. Digital tools are not widely used for court case management in Africa.

Although the number of countries using digital tools for court and case management is small, those countries tend to have more efficient systems.

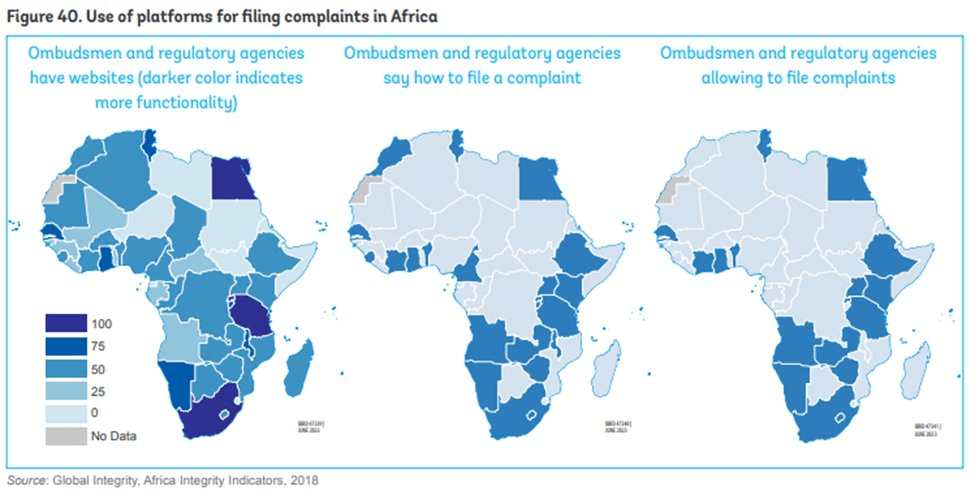

Several other applications of digital tools for better governance were examined. Unfortunately, some important uses are still the exception rather than the rule. Digital tools are not widely used for public consultations of draft legislation, and platforms for online reporting of corruption are less common in Africa than simple information provision.

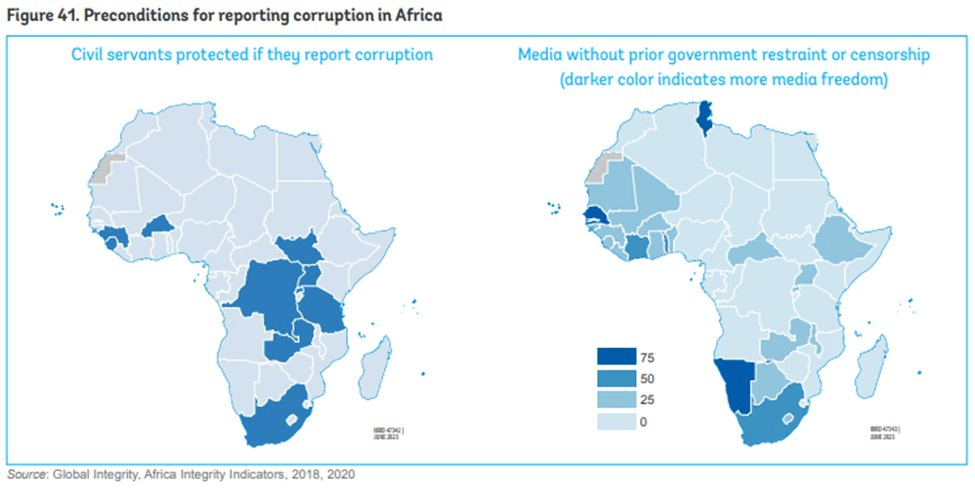

Returning to the theme of analog complements, the preconditions for successful corruption reporting platforms are weak in most countries. Civil servants need protections and the media must be free for such reporting platforms to work. And many key digital tools for detecting and preventing corruption are not used in most African countries. Digital development and governance development need to accompany each other to make inroads against corruption.

The bottom line? Shortcomings notwithstanding, countries in Africa with deeper use of GovTech tools have lower levels of corruption.

As noted at the beginning, this is part of a larger effort related to the digital economy and governance in Africa. Volume 1: Reaching the Potential for the Digital Economy in Africa: Digital Tools for Better Governance drew on background papers on adoption of eGP in Africa, vulnerabilities of ICT procurement to fraud and corruption, and ICT procurement in Africa. As a group, we thought of these as Digital for Governance.

The other part of this research project flipped this around, examining Governance of Digital. Be sure to check out Volume 2 Regulating the Digital Economy in Africa: Managing Old and New Risks to Economic Governance for Inclusive Opportunities and related background papers. They cover a wide range of topics, from market concentration, state involvement in the sector, taxation of the digital economy, data protection, cybersecurity, and more.

Some African countries are leading the way on digital tools for better governance. By paying attention to analog complements, they and others can reap the governance rewards of digital tools.